March 10 marked the 15th anniversary of the death of a famous American whose life was devoted to advancing our knowledge about language. He was, unfortunately, a controversial individual prone to drug use and violent outbursts, and wound up spending most of his life behind bars.

He also liked bananas.

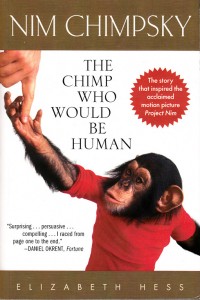

I’m talking, of course, about Nim Chimpsky (1973–2000), the second chimpanzee to be taught sign language. He is the subject of a fascinating and beautifully written biography, Nim Chimpsky: The Chimp Who Would Be Human by Elizabeth Hess. In 2011, the book was made into an award-winning British film called Project Nim.

Nim was the second chimpanzee to be taught sign language

Nim’s name was meant to recall American linguist Noam Chomsky, who had said, basically, that humans can speak and animals cannot. The “project” aimed to use Chimpsky to prove Chomsky wrong. The hope was that by being raised from birth and thus being exposed longer to human culture, Nim would outdo his predecessor, a wild chimp named Washoe, who had acquired a 350-word vocabulary in American Sign Language (ASL).

Under the direction of Herbert Terrace at Columbia University, Nim spent his first year in a home on New York City’s Upper West Side. His adoptive mother, Stephanie LaFarge, clothed him in diapers and raised him as one of her children. She taught him to make the signs for basic words — but the learning environment was very unstructured, and the documentation of Nim’s progress almost nonexistent.

To provide a more academic basis, Terrace set up a classroom in which Nim was given sign-language lessons and the results videotaped. Nim was entrusted to several of Terrace’s students and moved to an estate owned by the university. He had plenty of space to run around outdoors (on a leash). His housemates fed him pizza, let him smoke joints, and got him to help with the chores. Nim loved to wash the dishes, use a broom, and fold laundry (though he had trouble sorting it).

An identity crisis

Attempts to toilet-train Nim were less successful, and they were the sign of many more problems to come. Though only four years old in human years, Nim was a rebellious teenager in ape terms. He got up to some harmless mischief, but also became extremely obstinate and unmanageable. He destroyed everything in the house. His trainers, working in pairs, could barely get him to school, and once they did, he refused to pay attention.

Nim had never met another chimpanzee, but he was becoming one. He challenged his trainers in very physical ways in order to establish a hierarchy of social dominance like that in the ape world. He had gone from being a cute pet to a dangerous wild animal. He grew fangs, which, unlike those of circus chimps, were never removed. One trainer required 37 stitches for a bite on the arm. Another needed plastic surgery after Nim bit through her cheek.

Nim had never met another chimpanzee, but he was becoming one. He challenged his trainers in very physical ways in order to establish a hierarchy of social dominance like that in the ape world. He had gone from being a cute pet to a dangerous wild animal. He grew fangs, which, unlike those of circus chimps, were never removed. One trainer required 37 stitches for a bite on the arm. Another needed plastic surgery after Nim bit through her cheek.

Terrace saw no choice but to consider the experiment a failure and send Nim off to a medical research facility to live with other chimps who had outlived their usefulness. Some of them, too, had been taught a bit of sign language. From inside their cages in a windowless room, they tried desperately to communicate with their handlers, signing over and over the word “out”.

For Nim, this was doubly traumatic. He had no idea he was a chimp.

For Nim, this was doubly traumatic. He had no idea he was a chimp

A Boston lawyer aimed to free Nim by arguing in court that Nim should be treated like a human because he’d been raised as one. He even planned to have Nim testify. Before this could happen, however, New York University, which owned the research facility, agreed to let Nim go, and a well-meaning philanthropist moved him to his ranch in Texas.

Nim still lived in a cage — depressed and lonely — but at times he’d escape, go to a house on the property, watch TV and look at magazines. He never quite forgave the humans who had come and gone in his life. At age 26 — far too young for a chimpanzee — he died of a heart attack.

What was learned?

Nim’s experience with language raised more questions than it answered. The study was flawed from the beginning. Terrace’s students’ knowledge of ASL was not much better than Nim’s. Nim did not use grammar, but he could hardly have learned any. His vocabulary of only 125 signs limited him to basic and obvious statements. Instead of conversation, he tended to express demands, such as “Give me eat” and “Stone smoke now” (meaning “Give me a joint”). Terrace’s initial euphoria turned to a deep skepticism. Chimps like Nim weren’t speaking, he said; they simply knew that by making these signs, they could get their trainers to react. In his view, it was all imitation: monkey see, monkey do.

It’s also possible that Nim was a dud. Other apes, such as Koko the gorilla, have learned as many as 1,000 words and can distinguish between real and unreal situations. Only a handful of animals have ever communicated with us; the sample size is very small.

One striking difference in language use applies to all of them, though: apes don’t ask questions. They understand questions, but they don’t pose them. Why that is might be the biggest question of all.

Further reading

Read more about Nim in this article by his biographer, Elizabeth Hess:

Nim Chimpsky: the chimp who thought he was a boy (The Telegraph)

Read about the animal heroes who pioneered the US space program:

Remembering Albert (Fascinating America blog)