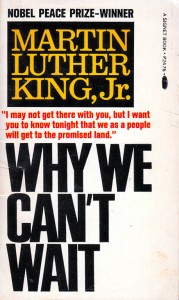

Among the aging paperbacks on my bookshelf is a thin volume from 1963 by Martin Luther King, Jr., called Why We Can’t Wait. King wrote this nearly 10 years into a civil-rights movement whose origin he placed in a Supreme Court decision in 1954. The book came years after the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott and several marches King had organized. It even came after his “I have a dream” speech filled the National Mall in Washington, DC, out to the horizon — a high-water mark in a people’s struggle for justice.

Among the aging paperbacks on my bookshelf is a thin volume from 1963 by Martin Luther King, Jr., called Why We Can’t Wait. King wrote this nearly 10 years into a civil-rights movement whose origin he placed in a Supreme Court decision in 1954. The book came years after the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott and several marches King had organized. It even came after his “I have a dream” speech filled the National Mall in Washington, DC, out to the horizon — a high-water mark in a people’s struggle for justice.

From King’s perspective, this movement hadn’t been a linear process. Things had reached a critical point, he said, near the end of 1962 and the beginning of 1963. Exactly 100 years had passed since Abraham Lincoln had declared an end to slavery in the United States. The arrival of this anniversary, said King, had led African-Americans to ask out loud whether they had indeed achieved the equality Lincoln had intended.

In 1963, with an entire system of segregation in place to keep blacks and whites apart, the answer to that question was obvious, and it was remedied in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Since then, two generations have passed, but again America faces a civil-rights movement that is starting to reach critical mass.

Two generations later…

As in the 1950s and ’60s, particular incidents are causing this to flare up. Last week’s protests in Baltimore, Maryland, revolved around the death of yet another unarmed black man during an arrest. (Such incidents, in a number of cities, have become so common that “unarmed black man” is now a meme.)

Gray’s crime was making eye contact with the police

Freddie Gray was no saint — he had a lengthy police record — but his crime on April 12 was making eye contact with police officers, then running away. The police caught up to him and found he was carrying a pocketknife. They put handcuffs and ankle restraints on him, shoved him into an empty van, and drove off without strapping him in. By the time the ride was over, Gray’s spinal cord had been severed; he soon died from this. An allegation by police that Gray had somehow caused his own injuries was just one of several statements that evidence appeared to contradict.

Similar cases in recent years have almost never led to any police officers being held to account — hence the unfocused anger of the protesters not just in Baltimore, but also New York, Philadelphia and other cities. But when the week ended, Maryland state prosecutor Marilyn Mosby made the surprising announcement that all six of the police officers involved in Gray’s arrest were to face multiple charges having to do with murder. She contradicted their claim that Gray’s pocketknife was an illegal type.

Ferguson was just the beginning

Various protesters in Baltimore had told the media that they were building upon last August’s protests in Ferguson, Missouri: demonstrating to put an end to racism and to achieve justice and opportunity for African-Americans. But while Ferguson painted a clear picture of older white men versus young black guys, Baltimore is different. Sure, the mostly black residents of that city’s poor, crime-ridden neighborhoods say they are routinely harassed by the police. But half of the officers involved in Gray’s arrest are black. The state prosecutor is black. The mayor is black. Baltimore’s representative in Congress is black. Both the outgoing and the new attorney general are black. Even the president is half-black.

This is about basic human rights

To pin everything on racism and see these latest developments in black and white is to miss the point. This isn’t about civil rights; it’s about human rights — about being considered innocent until proven guilty, about equal protection under the law, about respecting the dignity of even the shadiest individual, about the police not being able to do things the Geneva Conventions forbid, about transparency and accountability in public office, and about society’s obligation to set an example and remain civilized even if it feels it’s under attack.

Sadly, there is no Martin Luther King out there making this point. If there were, he might take a moment to reflect that this weekend marks a very important anniversary. On May 10, 1865, the Confederate States of America — an entire country founded on principles of injustice — ceased to exist when its president, Jefferson Davis, was arrested by officers of the United States. One hundred and fifty years later, where are we with regard to human rights?