My German friends are often amazed when I tell them I’ve been to their home town — whether it’s Darmstadt, Bremerhaven, Görlitz or any of dozens of smaller places. Many of them have traveled around the world without ever having explored much of their own country.

I wasn’t any different when I was growing up. The world I knew was 150 miles long and 20 feet wide: the highway between our house and my grandmother’s in Pennsylvania. Everything beyond that existed only on television or in storybooks.

As a student, I finally moved far enough away for things to be very different. Many of the people I met in Arizona referred to my part of the country as “back east”, in much the same way as immigrants to the US once referred to “the old country” in Europe. The distance was almost as great, the sense of living on the frontier just as vivid.

Where was I?

This new environment came with its own set of reference points. The flatness of Ohio, the mountains of West Virginia, and the mysterious entity that is Canada were all abstract and unfamiliar to native Arizonans, who instead regarded California, Nevada, and New Mexico (which I’d known only from Road Runner cartoons) as real places. Clearly, I had to get out and explore, even just to understand where I was.

I’d known the western US only from Road Runner cartoons

Students of mine who are now studying in the US are going through the same phase. Last week was spring break — a week without courses when students typically travel. I’ve been following their adventures as they travel to Florida and North Carolina, across the Southern states, or to California. Warm, coastal places are as popular as ever.

During my time in Arizona, the place to go was a particular town on the west coast of Mexico, which offered the necessary amount of cheap alcohol and debauchery. I instead decided to head as far as possible in the opposite direction. For spring break, I went to Idaho.

The road less traveled

Now, Idaho was not the major skiing destination it is today. It was mainly known for forests that produced a lot of paper and that gave the capital, Boise, its name (French boisé = forested) — and for the food crop featured in its official slogan, “Famous Potatoes”.

Remote and mountainous, Idaho was said to be a haven for “survivalists” — people who wanted nothing to do with the US government or even regular society. I figured that kind of fit my mood at the time.

The cheapest, and least direct, route was by train: westward from Tucson to Los Angeles, then northeast to Las Vegas and Salt Lake City, before turning northwest to Boise. Some of these cities were almost a day apart, making it possible to sleep on the train, and the cities themselves made for worthwhile stopovers.

How grand it was to arrive at Union Station in Los Angeles, the one seen in countless movies. Grander still to spend all night wandering through Las Vegas casinos, watching fortunes being made and (far more often) lost. In Salt Lake City, the genealogical library revealed the microfilmed records of my family’s arrival in the United States in the 1890s. And after all that came the incomparably pristine pine-forest air of Idaho.

Like royalty

The employees of the tourist information office in Boise had been waiting all winter for my arrival, and they welcomed me like royalty. I was their only tourist.

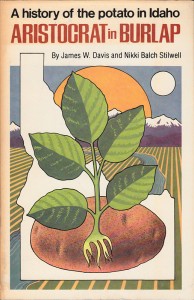

We chatted leisurely about the things to see and do in the capital, which mainly amounted to visiting the potato museum. Receiving their gift of a book about the history of Idaho’s potato industry was like being given the key to the city.

We chatted leisurely about the things to see and do in the capital, which mainly amounted to visiting the potato museum. Receiving their gift of a book about the history of Idaho’s potato industry was like being given the key to the city.

At every turn, my choice of “the road less traveled” brought rewards. Around lunchtime, I happened to be wandering through the state capitol building, where the potato lobby had set up a miniature cafeteria to showcase how versatile their product was. Mingling with the state senators, I was offered french fries with a choice of 10 different toppings — mayonnaise, shrimp sauce, you name it. Dessert was ice cream made with potato starch. The lobbyists invited me to go through the line again and again, and got a kick out of it when I did.

Before boarding the train for the three-day journey back, I realized this would all sound unbelievable to the folks at home. But what souvenirs could I find in a place with no tourism industry? I went to a supermarket and bought the largest baking potatoes I’d ever seen. I gave one to each of my friends in Arizona and told them my story.