At some point, it happens to all of us. The computer fails to save that important document we’ve been working on so long. A computer crash, a faulty hard drive, a USB stick pulled out too quickly, or just plain human error: the reason hardly matters when you’ve just seen your data disappear.

For journalists, this is a particular hazard.

At my old workplace, I watched intern after intern delete something by accident. But the editors weren’t immune either. The primitive network that connected the computers there could go down at any moment, and often did. A Post-It note with a drawing of a sad face and the words “Save! Save! Save!” tried to remind us of that.

In this office, all of us, at one time or another, have had to hurriedly reconstruct from memory an article we’d spent all afternoon working on. Often the reconstructed article was actually better than the original because we concentrated on the most important parts.

The other day, I came close to doing this with a document I use every day. There is a file I carry around that contains all my ideas and notes for this column and for other articles. Whenever I come across something I think I can use, I type it in. Whenever I read a newspaper article or see an online video I’d like to reference, I copy in the URL.

This file, having been copied and converted back and forth a hundred times among three different Word formats on three operating systems, had become so corrupted that it was no longer even visible. Of course I’d made backups regularly, but the most recent one was from three months ago. I’ve had a lot of ideas since then. Could I remember them all?

Our data is temporary

Fortunately, I had some sophisticated software that was able to locate and assemble all the missing parts of the file. The latest backup has been made, and all is well (until the next crash). But this has got me thinking. As our memories — our photos, music and personal documents — have become more portable, they have become more fragile. You can make backups, but even the backups aren’t safe.

I’ve seen several hard-disk drives wear out (when they start ticking, that’s the signal). CDs and DVDs can be scratched, warped or damaged by light, dust and heat. Even the flash memory on USB sticks and solid-state drives (SSD) wears out over time and can be destroyed by static electricity. And, of course, nothing is really immune to a power surge or a toddler.

Our data is temporary, and we migrate what survives.

But lest we despair, we need to remember that non-digital knowledge also fades. Think of old photographs, books whose binding has fallen apart, brittle cassettes and videotapes. Practically anything can fall victim to sunlight, moisture, mold, pets, children or overzealous cleaning staff, not to mention the more remote danger of flooding, theft, fire or war.

Lost and found

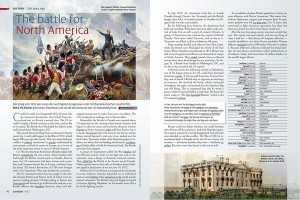

On the History pages of the June Spotlight, I write about the battle for North America in the War of 1812. When the British burned down Washington, DC, the entire Library of Congress was consumed by flames.

On the History pages of the June Spotlight, I write about the battle for North America in the War of 1812. When the British burned down Washington, DC, the entire Library of Congress was consumed by flames.

Fortunately, there was a backup. Thomas Jefferson had his own library — even larger than the one Congress had — and was able to donate nearly 6,500 books. The Library of Congress was restored almost overnight.

On that note: go home today and back up your data. You’ll be glad you did.

Language note: “The dog ate my homework” is an old excuse used by schoolchildren who didn’t do the work they’d been assigned. Teachers rarely, if ever, believed it. Today the expression is a humorous expression for a minor disaster happening outside one’s control — even though, with enough foresight, one should have prevented it.